About Vajrayana.co

Vajrayana.co is an online resource dedicated to making Tibetan Buddhist teachings and practices accessible to scholar-practitioners around the globe.

Our Vision

Features

Events Calendar and Forum

We are developing an events calendar that will catalog Tibetan Buddhist centers hosting both in-person and virtual events. This feature will enhance accessibility to teachings and foster community engagement through a dedicated forum.

Multimedia Library

Our comprehensive multimedia library will include:

- A collection of prayer books

- An archive of Dharma talks

- Practice guides and study materials

- Directories of monasteries, teachers, and organizations

This extensive archive aims to preserve the oral traditions of Tibetan Buddhism, making teachings available to a wider audience.

Language Resources

To promote the study of the Tibetan language, we are creating digital and printable flashcards and workbooks. These resources will facilitate both independent and group studies, covering both colloquial and classical Tibetan.

Feedback and Suggestions

We value community input. Our platform will incorporate feedback through surveys, allowing users to suggest improvements and new features that meet their needs.

Pecha Format

We uphold Tibetan Buddhist traditions by creating texts in pecha format, which is essential for the transmission of teachings. Our events calendar, library, and forum will foster a sense of sangha (community), helping to spread awareness of Buddhist traditions collectively.

Inclusive Learning

While our primary focus is on Tibetan Buddhism, Vajrayana.co serves as a resource for non-Buddhists as well. Our free educational materials, multimedia archive, and language learning tools are designed to create an inclusive space for exploration and personal growth.

Our Aspirations

We aspire to make a lasting impact on those we reach, acting as a catalyst for an international community of practitioners. Our goal is to facilitate cross-cultural sharing and learning, allowing diverse needs across traditions to be met.

Empowering Future Generations

Our hope is that every visitor to Vajrayana.co experiences greater understanding and realization, reducing suffering in their lives. We aim to inspire ongoing scholarship and practice, empowering individuals to contribute positively to their communities and beyond.

Our History

8th century AD: The renowned Indian Buddhist master Padmasambhava arrived in Tibet at the invitation of King Trisong Detsen. Padmasambhava helped establish the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism, which is the oldest of the major Tibetan Buddhist traditions.

11th century AD: The Kadampa school of Tibetan Buddhism was founded by the Indian Buddhist teacher Atisha. This school emphasized the importance of moral discipline and teachings on the path to enlightenment.

1357: Tsongkhapa, a renowned Tibetan teacher, founded the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. The Gelug school emphasized monastic discipline and the study of Indian Buddhist philosophy.

1578: The Tibetan spiritual and political leader Altan Khan gave the title “Dalai Lama” to Sonam Gyatso, establishing the lineage of the Dalai Lamas as the spiritual and political leaders of Tibet.

1642: The 5th Dalai Lama, Lobsang Gyatso, became the first Dalai Lama to hold both spiritual and political power in Tibet, uniting the country under his rule.

What is Vajrayana Buddhism?

Although Vajrayana shares with the Mahayana schools generally the view that we are already perfected and can awaken in a single lifetime, Vajrayana considers itself the fastest way to enlightenment. Its canon consists of texts known as the Kangyur (sutras and tantras considered to be the words of the Buddha) and the Tengyur (commentaries).

Vajrayana, like Mahayana, makes no distinction between samsara and nirvana: passions and aversions alike are embraced as skillful means to awakening. Though Vajrayana upholds the Mahayana bodhisattva ideal, its pantheon of celestial beings is more extensive, including a wealth of fierce protector deities and dakinis (female deities). Deity yoga—whereby a student takes on the identity of a chosen deity who represents enlightened qualities—is a central practice, guided by the guru, or lama, the master who initiates the student into esoteric practices. Ritual is key, including repetition of mantras (sacred syllables and verses), visualization of mandalas (sacred diagrams), sacred hand gestures (mudras), and prostrations. Ngondro, preliminaries, are prerequisites for higher tantric practices. The highest practices involve the symbolic union of the feminine (wisdom) and masculine (compassion) principles. Tantric practices are largely kept secret, to preserve the sanctity of the teachings and protect practitioners from energies they have not yet been trained to handle.

Of the four main schools of Tibetan Buddhism, the oldest is the Nyingma, whose founder is held to be the 8th-century Indian master Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche. Revered as the second Buddha, he is said to have hidden treasure texts (termas) to be discovered later both physically and in the mindstreams of tertons, or sacred masters. The Sakya school, headed by the Sakya Trizin (a hereditary title) is closely associated with the Hevajra-tantra, a text on nondualism, symbolized by the sacred union of the deity Hevajra and his consort. The Kagyu school traces its origins and practices to the Indian yogi Tilopa, the master Naropa, the translator Marpa, and his disciple Milarepa, Tibet’s poet-saint. The Kagyu school introduced the tulku system, the practice of recognizing reincarnations of great masters, thus continuing their lineages. The Gelug, the newest of the major Vajrayana schools, is a monastic sect incorporating elements of earlier schools; its most notable leader is the Dalai Lama.

Who better to explain the basics of Vajrayana than the Dalai Lama himself? Plus, learn about Kobo Daishi, founder of the Shingon school, a Japanese form of Vajrayana little-known in the West.

What is the history of Tibetan Buddhism?

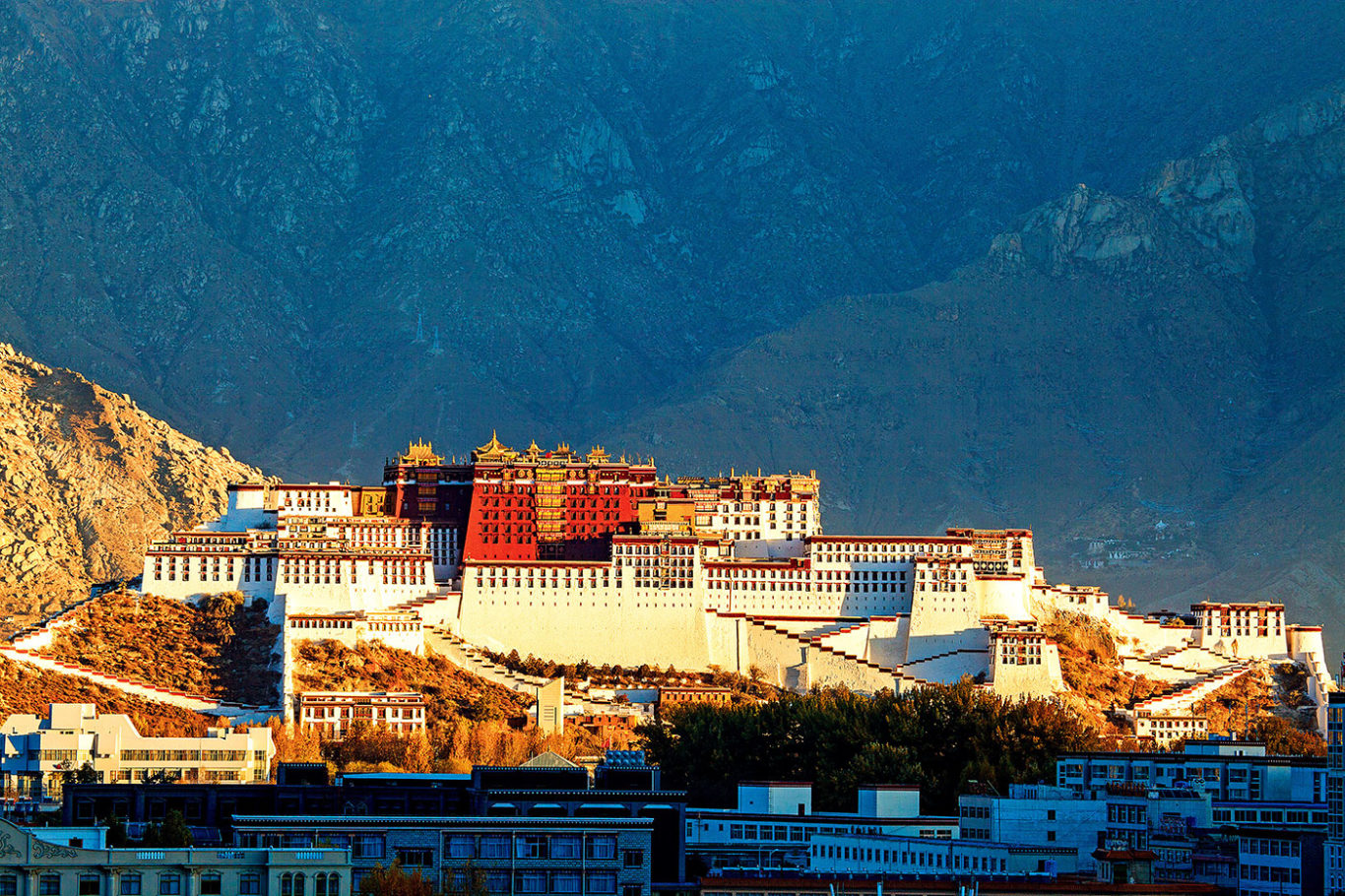

The Potala Palace in Lhasa was the winter palace of the Dalai Lamas from the 17th century to 1959. | View Stock / Alamy Stock Photo

Buddhism first came to Tibet in the late 7th century CE, when the first Tibetan king, Songtsen Gampo, asked Indian Buddhist teachers to come to the country and instruct his subjects, who mainly had been practicing local traditions that likely resembled the shamanic practices found in contemporary Central Asia. For several generations after Buddhism appeared in Tibet, it flourished under state sponsorship. In the mid 8th century, King Trisong Detsen invited Shantarakshita, abbot of the Indian Buddhist monastic university Nalanda, and the Indian master Padmasambhava (later known as Guru Rinpoche) to establish a monastic center in Tibet. They founded the Nyingma (“ancient ones”) school, the oldest of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism that exist today. King Trisong Detsen’s minister traveled to India to learn Sanskrit and translate Buddhist texts into Tibetan.

In the 9th century, King Langdarma is said by some accounts to have converted to Bön, a shamanistic tradition, after which he outlawed and persecuted Buddhists. After his death, Tibet fell into a period of civil war and political unrest.

Then in the 10th century, a second wave of Buddhist teachers from India was invited to Tibet, and in turn, Tibetan translators and scholars began traveling to India to receive teachings in various schools and lineages, including tantric ones, that had not reached Tibet previously. This brought about a set of new dharma transmissions called the Sarma or “new ones” traditions. Among them was the Kadampa school, founded by Dromton, chief Tibetan disciple of the Indian master Atisha. After that, many great teachers arose in Tibet, passing down the various Buddhist transmission lineages over the following centuries.

Tibetan Buddhism incorporated a range of practices from Indian Buddhism. These include the meditation practices of shamatha (calm abiding) and vipassana (insight), refuge vows, and monastic discipline from the Theravada tradition, and from the Mahayana, the bodhisattva vow, Pure Land practices, and lojong (mind training methods to awaken compassion). Tibetan Buddhist schools also incorporated the Vajrayana practices of ngondro (preliminary practices), mantra (sacred syllables and verses), mudra (sacred hand gestures), mandala (sacred diagrams representing the universe), and yogic discipline.

The transmission of Buddhism from India to Tibet was inspired by the lively and rich Buddhist atmosphere of late Indian Buddhism, from the 8th-century to the 12th century, when interactions among various traditions, philosophies and practices was at its height. By the 14th century, however, Buddhism had largely disappeared from its Indian homeland, in part due to invasions, institutional competition, and scarcity of the resources needed to support the large Buddhist universities of India. Fortunately, the Buddhist traditions that had taken root in other parts of the world survived. Tibet became the center of Buddhism in central Asia, as Tibetan Buddhism spread to neighboring Mongolia, Bhutan, Nepal, and parts of what are now Russia and India. Today, Tibetan Buddhism is the predominant religion of the Himalayan region.

What are the different schools of Tibetan Buddhism?

Scholars often divide the Tibetan Buddhist traditions into two main groups: Nyingma (older schools) and Sarma (newer schools). Nyingma refers to the traditions dating back to the earliest days of Buddhism in Tibet—specifically the teachings attributed to the 8th-century Indian tantra master Padmasambhava—revered as Guru Rinpoche—and his disciples. Sarma refers to the schools that arose during a second period of widespread Buddhist expansion following the death of King Langdarma (799–842 CE), who, legend says, persecuted Buddhists during his reign.

The Nyingma (“Ancient Ones”) tradition traces itself back to the earliest form of Buddhism in Tibet, and it is thus the oldest of the four major Tibetan Buddhist schools existing today. Modern historians hold that Tibetan Buddhism in the early period was not identified as “Nyingma” until some centuries later, when other, competing traditions arose. The Nyingma school emphasizes the practices taught by Padmasambhava, including the method for deep meditative insight called Dzogchen (Great Perfection). Nyingma practitioners also acknowledge a category of teachings called terma (treasure). They believe that Padmasambhava hid these teachings—in nature, in texts, in the mind stream of high lamas—to protect them for future generations and that Buddhist masters known as tertons (treasure revealers) would recover them centuries later.

The Kagyu (“Oral Tradition”) school traces its lineage back to the 11th-century Indian master Tilopa and his disciple Naropa. Tilopa was a tantric yogi known for a system of teachings on the nature of the mind called Mahamudra (Great Seal), which, according to legend, he received directly from the Buddha Vajradhara, an incarnation of the Buddha as a tantric deity. Naropa passed these teachings to the Tibetan translator Marpa, who taught them to the celebrated yogi Milarepa. A saint-like figure to the Tibetans, Milarepa transmitted the teachings to the 12th-century master Gampopa, and from Gampopa descend a number of distinct lineages—most surviving to this day—that are collected under the rubric of the “Dagpo Kagyu.” Many secondary branches of the Dagpo lineage emerged, but the main ones today, along with the Dagpo, are the Karma Kagyu, Drikung Kagyu, and Drukpa.

The Sakya (“Pale Earth”) school takes its name from Sakya Monastery, founded in the 11th century by Khon Konchog Gyalpo, a disciple of the Tibetan master Drogmi Lotsawa, a translator who had studied in India under Naropa and many other great masters. A member of the Khon family has headed the Sakya school in an unbroken line since then to the present day. The school is especially known for its main system of practice, Lamdre (Path and Its Result), which includes mantra practices and related teachings that trace their heritage back to the great Indian yogi Virupa. Sakya scholars such as Sakya pandita Kunga Gyaltsen (12th-13th century) and Goram Sonam Senge (15th century) have had a significant impact on Tibetan Buddhist philosophy.

Probably the most famous Buddhist figure today, His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, is the most prominent figure in the Gelug school, the youngest of the major Tibetan traditions. The meditation master and scholar Je Tsongkhapa established the Gelug school in the 15th century. He combined the 11th-century Indian master Atisha’s teachings on Lamrim (the Graded Path) with the 7th-century Indian master Chandrakirti’s Madhyamaka (Great Middle Way) teachings. The result was a new lineage that emphasizes philosophical analysis and monastic discipline alongside tantric practice.

All of these Tibetan schools, along with many sub-lineages, have survived to the 21st century.

The Tibetan Buddhist schools differ on specific points of philosophy and practice, and these differences, alongside socio-political pressures, resulted in periods of widespread sectarian violence in Tibet. Since the Tibetan diaspora began in 1959, leaders of the different Tibetan Buddhist schools have worked to establish good relationships among spiritual practitioners in the exile community and around the world.

What are some important texts in Tibetan Buddhism?

One of the many volumes of the Kangyur (“Translated Word”), one of the two Tibetan Buddhist canonical texts, is conserved at the Library of Tibetan Works & Archives in Dharamsala, India, the home of the Tibetan exile community in India. | Lucas Vallecillos / VWPics / Alamy Stock Photo

The Tibetan Buddhist literary tradition is vast. It includes a wide variety of early Buddhist scriptures, later Mahayana sutras, tantric texts, practice and ritual guides, autobiographies, and commentaries.

Between the 8th and 14th centuries, Tibetan scholars translated an amazingly broad array of Indian Buddhist texts into Tibetan. This accumulation was almost miraculously prescient, as in the 12th century, many Buddhist texts were lost when invading armies destroyed Buddhist temples and monastic universities in India. In fact, many Mahayana Buddhist works that were originally in Sanskrit survive only in Tibetan translation.

Perhaps the most important works are the Buddhist scriptural texts called the Kangyur and the commentaries and treatises known as the Tengyur. The Kangyur (“Translated Word”) is made up of some 1,169 texts attributed to the Buddha himself, with nearly all of the original texts being written in Sanskrit. The Tengyur (“Translated Treatises”), is made up of more than 4,000 commentaries and treatises by Buddhist masters, and here again, the vast majority of the original texts were written in Sanskrit.

Besides these canonical texts, Tibetan masters wrote important commentaries on the sutras and tantras, as well as works describing Buddhist practices for both monastics and laypeople. Among the most well-known of these are the terma (treasure texts) attributed to Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche), the 8th century south Asian master who helped bring Buddhism to the Himalayas. Tibetan Buddhists believe Padmasambhava hid these texts for future masters called tertons to find at the right time.

Bardo Thodol, or Book of Liberation Through Hearing in the Bardo, often known by the mistranslated title Tibetan Book of the Dead, is the most famous treasure text. A guide to the experience of death and rebirth, it was found and published by the terton Karma Lingpa (1326–1386).

Another important work is The Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, by the great Indian scholar Atisha (982–1054). This is the source of the Tibetan Buddhist lamrim, (stages of the path) literature, which ties together the various threads of Buddhist teaching transported to Tibet. Building on Atisha’s text is The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Lamrin Chenmo) by Tsongkhapa (1357–1419), a broad collection of oral instructions that present a comprehensive program for spiritual transformation.

The Way of the Bodhisattva by the Indian Buddhist master Shantideva (685–763), translated into Tibetan in the 9th century, is the authoritative guide to the bodhisattva path. The 37 Practices of a Bodhisattva by Gyelsay Togmay Sangpo (1295-1369) describes a fearless path of love and compassion accessible to monastic and lay Buddhists alike.

The Eight Stanzas of Thought Transformation by Langri Thangpa (1054–1123) and The Seven-Point Mind Training by Chekawa Yeshe Dorje (1101-1175) are two brief masterworks on how to transform one’s entire life by training the mind in love and compassion.

The Life of Milarepa and The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa by Tsangnyon Heruka (1452–1507) follow the singular story of Milarepa (1040–1123), whose journey from wealth to poverty to black magic to murder and finally to the Buddhist path and enlightenment demonstrates the redemptive power of the dharma.

An ambitious project is working to translate entire Tibetan canon into English over the next 100 years.

Who are some prominent figures in Tibetan Buddhism?

The revered 8th-century Indian tantric master Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche) appears in a Tibetan painting along with Mandarava and Yeshe Tsogyal, his accomplished consorts and disciples. | Sabena Jane Blackbird / Alamy Stock Photo

The early Tibetan king Songtsen Gampo is credited with introducing Buddhism to Tibet in the late 7th century through the influence of his Nepali and Chinese wives. He also is known for uniting Tibetan feudal lords, developing the Tibetan language, and founding the first Buddhist temples in Tibet. In the early 8th century king Trisong Detsen played a pivotal role in establishing the first Buddhist monastery at Samye in Tibet, inviting Padmasambhava and other South Asian masters to Tibet to facilitate building of the monastery.

Padmasambhava (also known as Guru Rinpoche) was an 8th-century Indian tantric master revered by Himalayan people as a “second Buddha.” He and his extraordinary female disciples (and consorts) Yeshe Tsogyal and Mandarava established the Nyingma (Ancient Ones) school of Tibetan Buddhism. Legend holds that Padmasambhava also made peace with local spirits and priests, placed dozens of termas (hidden teachings) around Tibet for discovery by future teachers called tertons and brought teachings on the Dzogchen (Great Perfection) system of practice to Tibet.

In the 10th century, the Indian master Atisha (980–1054) was part of a second wave of Indian Buddhists invited to Tibet following a period of religious persecution. His Tibetan disciple Dromton (1005–1064) founded the Kadampa school.

Marpa Lotsawa (1012–1097) brought what became the Kagyu tradition of Mahamudra (Great Seal) teachings and empowerments from India, and his disciple Milarepa (1028–1111) became a celebrated poet and yogi. Milarepa’s disciple Gampopa (1079–1153) wrote the seminal text Ornament of Precious Liberation and founded a major branch of the Kagyu school, Dagpo Kagyu.

Also at this time, Khon Konchok Gyalpo (1034–1102) founded the Sakya tradition, beginning an unbroken line of Khon family members heading the order. Another notable master of the tradition was Sakya Pandita (1182–1251), who is considered one of the greatest Tibetan Buddhist scholars because of his wide-ranging study of the philosophy, logic, language, astrology, and poetry of his day.

The remarkable female yogini Machig Labdron (1055–1149) founded the chöd lineage of teachings and ritual-offering practices based on her fearless interpretation of the Prajnaparamita (Perfection of Wisdom) sutras.

Tsongkhapa (1357–1419), an accomplished master and scholar, gave rise to the Gelug school. He also wrote the famous texts Lamrim Chenpo and Ngakrim Chenmo outlining a path joining the sutra and tantra traditions.

Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye (1813–1899), one of the most prominent Tibetan Buddhists of the 19th century, compiled a five-volume compendium of practices and teachings from across Tibetan Buddhists lineages. He and his peers, Chokgyur Dechen Lingpa (1829–1870) and Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (1820–1892), are considered paragons of the non-sectarian Rime movement.

In the 20th century, the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso (b. 1935), gained worldwide renown following his escape from Chinese-controlled Tibet amid the 1959 Tibetan uprising and has since become perhaps the most recognizable Buddhist figure. The Dalai Lama is a prominent figure in the Gelug school and spiritual leader of the Tibetan people. He and other exiled religious leaders, including the 16th Karmapa (1924-1981), the 41st Sakya Trizin (1945-present), and Nyingma leader Dudjom Jigdral Yeshe Dorje (1904-1987), established Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and centers in exile in India and eventually around the world.

What is Buddhist tantra?

Think tantra is all about sex? Think again! Tantra is an ancient Indian religious movement that seeks to harness a wide variety of experiences and mental and physical energies for use on the path to enlightenment. Tantra practitioners believe that by engaging in these esoteric practices under the guidance of a teacher one can attain awakening within just one lifetime. Tantric practices are numerous but include working with sound through mantra (sacred words and phrases), with gesture through mudra (ritualized sacred hand gestures), with sight through visualizations and mandalas (diagrams of the universe), and with vital energies through meditation and yoga.

Tantra literally means “thread,” “loom,” or “warp,” and in the Vajrayana view, tantra texts weave together “strands” of sutras. Vajrayana holds that the tantras, like the sutras, were taught by the historical Buddha in his tantric form (known as Vajradhara) or by other enlightened beings. Theravada, on the other hand, considers the tantras to be later additions and rejects them. Historically, Buddhist tantras probably first appeared in India between the 3rd and 6th centuries CE, and new tantras continued to appear through the end of the first millennium, eventually spreading to many parts of Asia. Today, Buddhist tantra is primarily found in all of the Tibetan lineages and also in Japanese Buddhism, especially Shingon. Tantric texts and practices, some with considerable resemblance to Buddhist versions, are also found in Hinduism.

Tantra is a method for realizing the ultimate nature of reality, especially when “reality” is understood in terms of the nature of mind itself. The basic idea is that our suffering arises from our misapprehension of reality: we falsely take phenomena that are “empty” of any reality to be objectively real, separate, and unchanging. Tantra, however, is not just about seeing the nature of reality. It is also about the full manifestation of one’s buddhanature, our intrinsic potential to become buddhas ourselves.

Tantric practice involves various stages, some that make use of elaborate rituals and visualizations. An example is the practice of Chenrezig (Skt. Avalokiteshvara) the bodhisattva of compassion. One begins by visualizing Chenrezig as a figure made of light above one’s head. After supplicating Chenrezig, one visualizes themself as Chenrezig, seeing their mind as identical to the deity’s. In this way, a practitioner is said to “take the result as the path,” which means that one identifies directly with buddhas and bodhisattvas, visualizing oneself as the deity (yidam)—a key aspect of tantra. The meditation closes with the deity dissolving into emptiness, allowing the mind to rest in its own nature.

This style of practice requires a subtle and nuanced view of oneself and the world, so it is entered gradually. Known as guru yoga, it begins with forming a bond (Skt., samaya) with a teacher and completing extensive ngondro (preliminary, or foundational) practices. The teacher then gives the student empowerment, or authorization to visualize oneself as the meditation deity, as well as authorization to recite the text (reading transmission) and practical instructions on how to meditate on the yidam.

Although the samaya bond urges the student to maintain a pure view, or “sacred outlook” of the teacher and fellow disciples, the ultimate samaya is to maintain an awareness of the true nature of one’s mind and surroundings. It is this continual awareness that dispels confusion and fosters awakening.

What is the role of retreat in Tibetan Buddhism?

A monk sits in meditation on retreat at Lapchi Snow Mountain, where tradition holds the great tantric master Milarepa meditated. | piotr sadurski / Alamy Stock Photo

Retreat has been a central aspect of monastic practice since the dawn of the sangha, when the Buddha instituted an annual three-month retreat during the rainy season for all monks and nuns. Retreats can be of any length and are usually entered into by a student under the direction of a teacher who has mastered the techniques that will be practiced. The goal of withdrawing from everyday life is to practice physical and meditative openness and simplicity for the benefit of all sentient beings.

Tibetan Buddhism embraces retreat and has instituted a variety of different approaches to it. Although these not all of these forms are unique to Tibetan Buddhism, they tend to be emphasized more.

Vajarayana’s tantric practices of yogic discipline require periods of isolation so practitioners can immerse themselves in the sacred and transformative world of the buddhas and bodhisattvas. Isolation is also supportive for serious practitioners of meditative insight disciplines like Dzogchen (Great Perfection) and Mahamudra (Great Seal), which are aimed at seeing through the illusions of samsara. Vajrayana practitioners of many traditions, but particularly Dzogchen and Mahamudra practitioners, have been known to undertake long retreats in caves and on mountainsides.

In the 19th century, the Kagyu master Jamgon Kongtrul began the tradition of the three-year retreat for Mahamudra practitioners, who train in the core practices of sutra and tantra for three years, three months, and three days. Kongtrul derived that timeframe from the teachings in the Kalachakra (Wheel of Time) tantra, an important Vajrayana text that defined that as the amount of time required for a practitioner to properly develop their wisdom and karma through undistracted meditation.

Since then, other Tibetan Buddhist traditions have adopted the three-year model, and in modern times completing it has become a requirement for aspiring Buddhist teachers before they can be given the title of Drupay Lama (lama of the retreat).

Another form of long retreat is the solo “wandering retreat” used by masters such as Milarepa in the 12th century, as well as practitioners in more modern times, among them Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche in the 21st century.

Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, the second Western woman to ordain in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, famously did a 12-year solo retreat in a remote mountain cave; she discusses the experience in this interview.

Where is Tibetan Buddhism practiced and how did it come to the West?

Despite its name, Tibetan Buddhism is practiced not only in Tibet but across the Himalayan region and around the world, in Asia, Europe, Africa, North and South America, and Australia. But before the 20th century, Tibetan Buddhism was virtually unknown in the West.

In the 1920s, 30s, and 40s, a handful of Europeans managed to evade Tibet’s ban on foreign visitors, and travelers like Alexandra David-Néel, Lama Anagarika Govinda (born Ernst Lothar Hoffmann), and Heinrich Harrer, who became the 14th Dalai Lama’s English, geography, and science tutor, wrote books about their experiences. In the early 20th century, Christian missionaries attempted unsuccessfully to bring Christianity to Tibet, while the British, who were ruling India at the time, launched a short-lived invasion in 1903. But the Tibetan Buddhist tradition began to reach more Westerners only after the 14th Dalai Lama and other Tibetan leaders fled Tibet in 1959 following the Chinese invasion.

The exiled Tibetan lamas settled in India, where they re-established religious and political institutions. There, a new generation of foreign visitors encountered Tibetan Buddhist teachers and teachings. A few Westerners, including the American Buddhist scholar Robert Thurman, took ordination as Tibetan Buddhist monastics, with some later returning home to establish practice communities in their countries of origin. Books on Tibetan Buddhism began to appear in English, and importers rushed to work with craftspeople in India and Nepal to feed a growing interest in Tibetan Buddhist practice and study materials.

In the late 1960s and 70s, Tibetan monks and lamas living in India began accepting invitations to study abroad and teach interested dharma students in Europe and the Americas. Later, as interest in the Tibetans grew, Tibetan scholars, including Geshe Lhundup Sopa, began filling teaching posts in the West, and Tibetan language and literature became topics of study in colleges and universities. The Dalai Lama traveled to the West for the first time in 1979, before becoming a worldwide symbol of Tibetan Buddhist philosophy and practice when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989.

Tibetan refugees, meanwhile, were settling in many countries in the West, where Tibetan Buddhist exiles were forming practice communities and offering retreats. As more Americans and Europeans completed formal training at these centers, Western-born lamas and teachers began to fill dharma seats at Tibetan Buddhist centers in the West and even in Asia.

Today, all the major schools of Tibetan Buddhism have dharma centers on every continent but Antarctica.

What will it take to establish a truly Western dharma? In “It Takes a Saint,” Tai Situpa Rinpoche, a prominent Kagyu leader, writes it will take one Westerner attaining full enlightenment. You can also read Tibetan author Bhuchung D Sonam’s reflection on the Tibetan diaspora’s enduring struggle, and learn about a flourishing Tibetan sangha in Ohio led by Lama Kathy Wesley.

What’s the difference between a monk, a nun, a tulku, a rinpoche, and a lama?

A Tibetan Buddhist who becomes a monk or nun leaves home and takes vows to lead a life of contemplation, meditation, renunciation, and simplicity. Many move to monasteries or nunneries to study and practice as part of a sangha, or monastic community. Others, especially in places where there are no abbeys in their lineage, live among lay dharma practitioners, but in principle they are meant to return periodically to a monastery. Monastics—and less frequently, lay practitioners—also may choose to go on retreat and spend months or years in isolated hermitages or caves. Tibetan monastics, as a rule, do not marry. An exception is the Sakya school’s lineage of married monk-teachers dating back to the 11th century. (In several Tibetan lineages, revered teachers do not necessarily hold formal monastic ordination, and they therefore may be married and have children.)

Lama is the Tibetan translation of the Sanskrit guru (“teacher”). As with the Sanskrit term, Lama is loosely defined, and historically, it is not a formal term or title that is conferred on a practitioner, although in more recent years the practice of bestowing lama as a title is not unheard of. In its more traditional usage, lama especially refers to one’s personal teacher, and by extension it therefore can also be used to refer to any Buddhist practitioner or teacher who is worthy of respect. In this more general usage, lama is therefore often reserved for persons of some renown, or who have completed a notable practice such as a long-term retreat. But it can even be used just to refer to an ordinary monk or nun, or an ordinary lay tantric practitioner.

The title Rinpoche, which means “precious one,” is used in much more precise ways. Reincarnated teachers or tulkus (described below) are invariably given the title of Rinpoche, as are other revered figures such as abbots of monasteries and teachers who guide long-term retreatants. As with persons called lamas, a rinpoche can be either a monastic or a layperson.

The leaders of a Tibetan Buddhist lineage sometimes recognize a person as a tulku, the reincarnation of a great master of the past. Rather than escape the cycle of rebirth and enter nirvana, tulkus are believed to have made a conscious choice to be reborn so they can benefit other sentient beings and guide them toward enlightenment. The Dalai Lama is the most famous tulku, as he is believed to be the 14th incarnation of the first Dalai Lama, who lived six centuries ago. Tulkus are usually identified as young children, sometimes through elaborate rituals and tests, and then brought to their predecessor’s monastery to be educated by private tutors. A tulku can be male or female and can live as a monastic or a lay practitioner. Many tulkus serve as abbot of a monastery, and tulkus often inherit property, generally known as a labrang, from their previous incarnation.

Do you have to learn the Tibetan language to practice Tibetan Buddhism?

Not at all. Since the exodus of Tibetans from their homeland in 1959 (in the wake of the Chinese occupation), and subsequent travel by Tibetan Buddhist teachers to virtually every continent in the world, the important practice texts of all the great Tibetan traditions have been translated into other languages—including English and Mandarin—so that students in every part of the world can read and understand them.

Most Tibetan teachers these days use hybrid, or combination, practice texts that include the original Tibetan script, a transliteration (phonetic spelling so that you can pronounce the Tibetan words), and a translation into the language of the reader.

When Tibetan teachers first traveled to Western countries in the 1960s, they encouraged students to learn to read Tibetan script, which was developed in the 7th century by Thonmi Sambhota (a Tibetan imperial minister) at the emperor’s request. (Tibet at that time had no alphabet, so Thonmi traveled to India and created a Tibetan alphabet based on Indic letters.) Since the written language was initially developed to translate Buddhist texts from Sanskrit, many Tibetan teachers felt that the script itself was blessed, and that blessing could be imparted to anyone who used it.

But in response to requests from new students in the West, translation of Tibetan Buddhist texts into English and other languages became a priority. Tibetan teachers in all lineages began training translators and producing texts that could be read and used by Western dharma students. Similar requests were met in Taiwan and other Asian countries, and Tibetan texts increasingly became available in new languages.

By the turn of the 20th century, texts were being produced that allowed students to receive the direct blessing believed to result from reciting prayers and practices in their original languages (using transliteration) and at the same time receive the clear meaning of texts in the dharma students’ own languages.

Today, Tibetan language study is offered in colleges in various countries. Monasteries and dharma centers also have translation schools and committees to help deepen students’ understanding, train translators to help with the interpretation of oral teachings and written works, and prepare practice and study texts for new generations of dharma practitioners.

But for the average student of Buddhism and daily practitioner of Tibetan chants and meditation, learning the Tibetan language is not a requirement, just as you don’t need to know Sanskrit and Japanese to join a Zen sangha or Pali to follow a Thai Forest Tradition teacher.

Chinese authorities have cracked down on Tibetan language instruction in Tibet; one language advocate, Tashi Wangchuk, is serving five years in prison for asking China to enforce its own laws on offering Tibetan language classes.

Do you have to learn the Tibetan language to practice Tibetan Buddhism?

Not at all. Since the exodus of Tibetans from their homeland in 1959 (in the wake of the Chinese occupation), and subsequent travel by Tibetan Buddhist teachers to virtually every continent in the world, the important practice texts of all the great Tibetan traditions have been translated into other languages—including English and Mandarin—so that students in every part of the world can read and understand them.

Most Tibetan teachers these days use hybrid, or combination, practice texts that include the original Tibetan script, a transliteration (phonetic spelling so that you can pronounce the Tibetan words), and a translation into the language of the reader.

When Tibetan teachers first traveled to Western countries in the 1960s, they encouraged students to learn to read Tibetan script, which was developed in the 7th century by Thonmi Sambhota (a Tibetan imperial minister) at the emperor’s request. (Tibet at that time had no alphabet, so Thonmi traveled to India and created a Tibetan alphabet based on Indic letters.) Since the written language was initially developed to translate Buddhist texts from Sanskrit, many Tibetan teachers felt that the script itself was blessed, and that blessing could be imparted to anyone who used it.

But in response to requests from new students in the West, translation of Tibetan Buddhist texts into English and other languages became a priority. Tibetan teachers in all lineages began training translators and producing texts that could be read and used by Western dharma students. Similar requests were met in Taiwan and other Asian countries, and Tibetan texts increasingly became available in new languages.

By the turn of the 20th century, texts were being produced that allowed students to receive the direct blessing believed to result from reciting prayers and practices in their original languages (using transliteration) and at the same time receive the clear meaning of texts in the dharma students’ own languages.

Today, Tibetan language study is offered in colleges in various countries. Monasteries and dharma centers also have translation schools and committees to help deepen students’ understanding, train translators to help with the interpretation of oral teachings and written works, and prepare practice and study texts for new generations of dharma practitioners.

But for the average student of Buddhism and daily practitioner of Tibetan chants and meditation, learning the Tibetan language is not a requirement, just as you don’t need to know Sanskrit and Japanese to join a Zen sangha or Pali to follow a Thai Forest Tradition teacher.

Chinese authorities have cracked down on Tibetan language instruction in Tibet; one language advocate, Tashi Wangchuk, is serving five years in prison for asking China to enforce its own laws on offering Tibetan language classes.

Why are there so many images of buddhas, godlike creatures, and demons in Tibetan art and temples?

Tibetan Buddhist thangka paintings depict (left to right) the Buddha, a wrathful deity, and a peaceful deity. | Charles O. Cecil / Alamy Stock Photo

Tibetan temples are decorated with a wide variety of figures: mythological animals; fierce protectors armed with weapons; and peaceful, meditating figures clothed in silks and jewels and sitting on lotus flowers with moon-disk seats.

Many of the beings we may think look like gods or demons are actually buddhas and bodhisattvas appearing in either a peaceful, semi-wrathful, or a wrathful form. Peaceful forms attract and inspire the dharma practitioner; wrathful forms provide a feeling of protection from negativity—including the practitioner’s own negative emotions and states of mind.

Where do these representations come from? Although the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, is revered in all schools of Buddhism, he is not the only person to have achieved spiritual awakening, or buddhahood. The teachings say that all beings have the potential to reach buddhahood, and the Mahayana sutras and Buddhist tantra texts tell the stories of many practitioners who have attained awakening in various eras and places. These “awakened ones” are said to manifest in different ways, in accordance with their aspirations and the needs of others.

Chenrezig (the bodhisattva of compassion) and Tara, for example, are two peaceful bodhisattva forms. They are richly dressed in silks and jewels, symbolizing all the qualities of enlightenment, and their crowns are adorned with five gems, symbolizing the fact they transformed five negative mental afflictions into five types of wisdom. Their peaceful, loving gazes are like that of a parent for her child.

Vajrayogini, one of the buddhas described as “semi-wrathful” (having both peaceful and wrathful qualities), wears jewelry and carries a cup made of human bone. She is the embodiment of absolute wisdom: having overcome the fear of death, she can now bear the symbols of death as ornaments. Her blade held aloft represents the wisdom that cuts through delusion, and she is depicted trampling a body—the corpse of ego-fixation.

Tibetan teachers explain that just as

there are countless sentient beings, so there are countless doorways to

enlightenment that respond to the various needs and inclinations of

different beings. The many buddhas and bodhisattvas in Tibetan

iconography reflect these differences in orientation, and they provide

inspiration to many different kinds of dharma practitioners to follow

the Buddha’s path of self-knowledge and awakening.

We organize regular meetings for mentors who want to share their wisdom and for apprentices who want to find enlightenment.

Buddhist religion is not imposed on our guests. You do not even have to be a Buddhist to come and stay as long as you wish. We teach the way of thinking, not the rules of life.